Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal said 30 more services will be included in the project in the next one month and the number will rise to 100 in two-three months.

For weeks, Sudesh Kumar had been having a sinking feeling. His driving licence was about to expire. He knew the misery that lay ahead: taking time off his property rental business to queue for hours in the muggy heat, facing the chaos in the squalid government office, and finally capitulating to the tout who promised to push through his application – for a price.

This time, it turned out to be as easy as ordering pizza.

Kumar dialled 1076 and booked an appointment for a person from the Delhi government to come to his home. The two men sat on the sofa of Kumar’s small house in Chattarpur while the representative took down Kumar’s details on a tablet, filled out a form, uploaded his ID card and photograph and took his biometric data. Kumar paid the fee with his credit card.

“It was over in 15 minutes. I couldn’t believe how easy it was. In a few days’ time, my new driving licence will come through the post. Dealing with the government has turned from hell into heaven,” said Kumar.

Other residents of the Indian capital are equally stunned. The Delhi government, ruled by the Aam Aadmi (Common Man) party, has rolled out a radical scheme, at a cost of 150m rupees, to free the city’s 18 million residents from having to visit government offices – and reduce corruption.

Forty services including applications for driving licences, marriage certificates, pensions, and water connections are now being delivered to people’s doorsteps. A battalion of young male and female foot soldiers (“mobile sahayaks”), armed with tablets and cameras, carry out the appointments, whizzing around the city on scooters. The fee is set deliberately low, at 50 rupees (50p), and the service is available from 9am to 9pm, seven days a week. In three months’ time, the list of services will be extended to 100. A private company, VFS Global, which handles visa and passport services, has been hired to run the project.

Delhi’s chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, called the project a “revolution in governance”. His deputy, Manish Sisodia, said the aim was to ease the life of the common citizen.

“Usually the citizen goes to the government,” said the minister for administrative reforms, Kailash Gahlot. “We wanted to reverse this and take the government to the citizen. People waste so much time to get simple documents.”

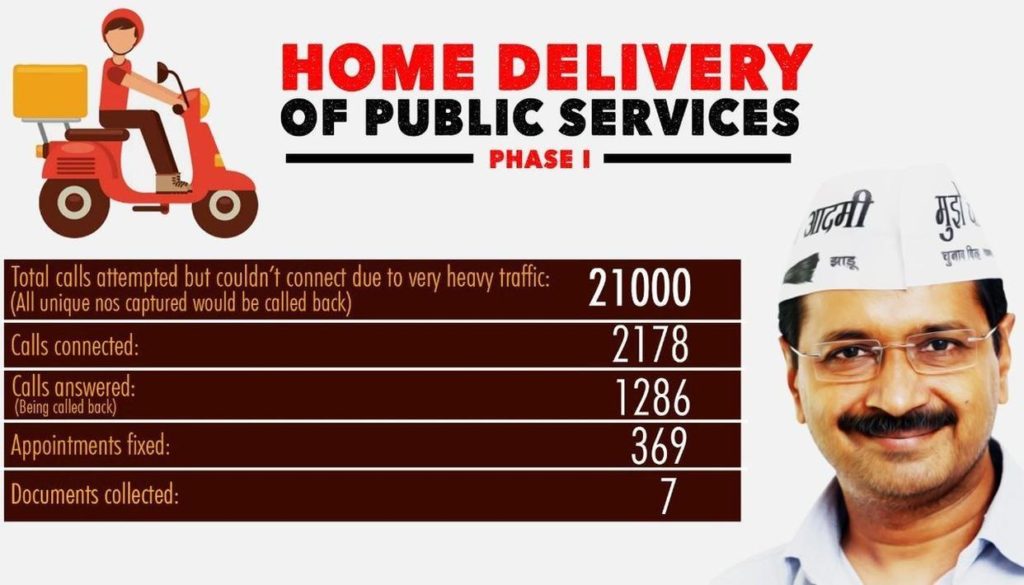

On day one, the helpline received 21,000 calls. Of these, only 2,728 were answered, and about 370 home visits were made. The government reacted to what it called the “enormous response” by increasing the number of telephone operators from 40 to 150 and the number of lines from 50 to 200 in two days.

Some critics worry that the 50-rupee fee is simply too low to sustain the scheme. Gahlot said that if the costs turned out to be unviable for VFS Global, the government would make up the difference, to ensure the project’s long-term viability.

There have been teething problems. Trilok Sharma, a marketing agent in Janakpuri who wanted to apply for a new water connection, found his mobile helpers could have done with more training. “They didn’t seem familiar with the software or the options it kept showing, nor with government rules. I would have preferred more experienced people to handle it. It would be quicker. That said, it’s a wonderful thing to have happened to the city,” said Sharma.

Internet problems are also common. When mobile helper Pankaj Khanna turned up at the home of commerce student Riddhima Gauba in Saket to take her application for a learner’s licence, the signal was so poor they had to leave the living room and stand on the balcony. Even then, it took him some time to upload Gauba’s application and credit card payment. And even when the internet is working, the government server can be slow.

For Sanjeev Oberoi, a technical manager with a US multinational, visiting a government office was synonymous with torture. It often entailed waiting for hours and reaching the counter only to find the official had gone to lunch or left for the day. But when he applied for a duplicate driving licence sitting in his Greater Kailash home this week, the experience, he said, “was a dream”.

Oberoi is one of those who fears the low fee will make the operation unsustainable. “They should charge more so that they can sustain it long term. It’s too good to endanger. It’s a great revolution in our lives and must be protected,” he said.